The Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897-1899

🇧🇪 How a bunch of guys froze themselves into the Antarctic pack ice over winter and survived through regular walkies, raw penguin meat and drawing each other's bums.

Warning: This page contains mentions of some human death, a lot of animal death, and jokes about Belgium.

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897-1899 is my favourite Antarctic expedition. I love it so much. I think it's amazing and I've been boring people with it ever since I found out about it.

The expedition is noteworthy for a few reasons. It was the first time on record that a group of humans spent a full winter within the Antarctic circle, and the scientists on board brought back a wealth of observations. They recorded a full year's worth of meteorological data and evidence of continental drift. They discovered over 110 new plant and animal species, including Antarctica’s largest strictly terrestrial animal, Belgica antarctica (a midge). The results of their research (including thousands of specimens covering more than 400 species) took 40 years to fully analyse. Even now, NASA scientists are studying the expedition as a model for how humans could survive long space missions without totally losing it.

It was also kind of a shitshow, and frankly it's a miracle these people didn't all get themselves killed. (Which I suppose is what makes any of these expeditions interesting.)

Whose idea was this anyway?

Baron Adrien Victor Joseph de Gerlache de Gomery was born into the Belgian aristocracy in 1866. He hungered for glory (which was fashionable) but also for the sea (which was unfashionable, as Belgium didn't even have a military navy at the time).

De Gerlache's first instinct for glory was to volunteer to go to the Congo so he could join in on all the atrocities Belgium was committing at the time, but King Leopold II said no. So in 1894, he decided he'd go even further afield: Antarctica!

At the time, Antarctic exploration had been in a lull for several decades. In the 1840s, James Clark Ross took the Erebus and the Terror down to Antarctica, confirmed there was indeed a continent under all that ice, made some scientific observations and got a lot of stuff after himself (including the Ross Ice Shelf, the Ross sea, Ross seals, Ross Island and James Ross Island – yes, those are two different islands). But both ships were subsequently lost in Franklin's disastrous Arctic expedition a few years later, which everyone generally agreed was a bad vibe, and the scientific world broadly lost interest.

However, in the 1890s, hype around Antarctica began to build again. Commercial whaling had decimated Arctic whale populations, and several whaling ships ventured to the opposite pole in search of better hunting grounds. People had begun to speculate this untapped continent might have other valuable resources, if only someone could get past all the ice. And while the Erebus and the Terror had been powered only by their sails, nautical technology had moved on. Steam-powered ships might make a better go of it.

De Gerlache decided to aim high and declared that he would be the first man to reach the southern magnetic pole. He managed to raise enough money to fund an expedition, promising his backers a wealth of scientific discovery, but more importantly, GLORY TO BELGIUM.

The Belgica

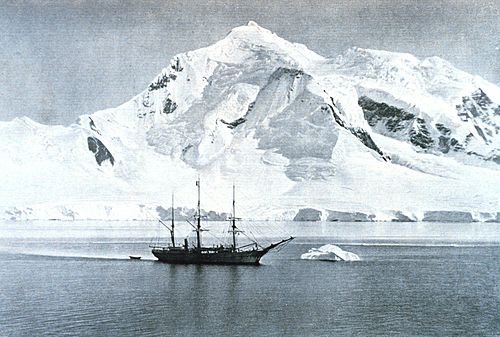

Funded by the Royal Belgian Geographical Society, the Belgian government and an assortment of rich people, de Gerlache bought a Norwegian whaler called the Patria, had her refitted as a research ship, and renamed her the Belgica.

The Belgica was built to operate in the ice, with a reinforced prow and a 35-horsepower steam engine.

Good-looking ship, imo.

The people of the Belgica

With the Belgica preparing to set sail, de Gerlache's next task was to hire a crew. Unfortunately, he had two conflicting requirements:

- Hire a crew with extensive polar nautical experience

- Hire as many Belgians as possible

Belgium was not exactly known for its nautical prowess. In fact, the Belgian navy had been abolished more than 30 years earlier, in 1862.

However, given that the entire expedition was focussed on bringing glory to Belgium, de Gerlache felt like he needed to stack his crew with as many Belgians as possible. Sure, there were a lot of Norwegians who might be great at that sort of thing, and de Gerlache begrudingly hired some of them. But this wasn't about them. It was about Belgium!!

So who did de Gerlache hire? Let's meet some of them.

Georges Lecointe, captain

Lecointe was a Belgian officer who had been seconded to the French navy and sailed the world. He'd also published courses on astronomical navigation, and, most recently, an entire treatise on why Belgium needed a military navy again.

Overall, a very solid pick for the expedition's second-in-command. Let's see if de Gerlache can keep up his winning streak.

Henri Somers, chief engineer

Henri Somers was also a Belgian – hooray! De Gerlache nails it again!

Unfortunately, when the Belgica docked in Antwerp, Somers decided to go on a drinking binge and got absolutely wasted, in public, in his uniform, for two days straight.

De Gerlache was forced to sack him for embarrassing the expedition.

Joseph Duvivier, chief engineer

Another Belgian (huzzah!), Duvivier was initially hired on as a mechanic. However, after Somers was sacked in disgrace, he was promoted to chief engineer.

With such a great responsibility, you would hope that Duvivier knew his stuff. Let's see the letter of recommendation from a former boss that got him hired:

"It is possible that Mr Duvivier might figure out how to work a very simple engine, like the Belgica's, but I cannot guarantee it"

If you think this does not bode well, you'd be right. Under Duvivier's expert watch, the Belgica broke down almost immediately. Even more humiliatingly, the ship had to moor right next to the king's yacht, just days after he'd supposedly waved them off on their journey. The king pretended not to recognise them.

At this point three other crew members, including another mechanic, decided to dip before the situation deteriorated any futher and quit in rapid succession.

De Gerlache demoted Duvivier to his old job and reluctantly rehired Henri Somers as chief engineer. It wasn't like the Belgica had left him far behind anyway.

Albert Lemonnier, cook

A Frenchman. Not ideal, but presumably you couldn't go too far wrong with a French cook.

Lemonnier was very successful in bringing the crew together. This was because everyone else, regardless of nationality, absolutely hated him. While there was often friction between the Belgian and Norwegian sailors, they could all agree on one thing: this guy sucked.

This mounting tension culminated in a massive brawl off the coast of Uruguay, during which Belgian sailor Jan Van Damme punched Lemonnier in the face. Everyone else agreed the fight was Lemonnier's fault. De Gerlache decided to fire him too.

Jan Van Damme, cook

Stepping into the shoes of the man he'd punched, Van Damme had one distinct advantage over Lemonnier: being Belgian.

Unfortunately, he caused even more trouble than Lemonnier. Van Damme's tenure as cook lasted until the Belgica reached Chile, at which point he became so drunk and mutinous that de Gerlache was forced to call in the Chilean navy for backup.

Van Damme and several others were fired for insubordination and escorted off the ship. Among them was mechanic-turned-chief-engineer-turned-mechanic Joseph Duvivier, who had since managed to get himself fired and rehired for drunkenly insulting a Brazilian admiral.

The ship's steward Louis Michotte took on the job for the rest of the journey, and by all accounts wasn't very good at it.

But while the expedition had run out of cooks, it had not run out of Cooks.

Frederick Cook, doctor

Cook was an American, but what he lacked in Belgianness, he made up for in enthusiasm. He wrote to de Gerlache several times begging to join the expedition, and since he was actually quite well qualified, de Gerlache finally agreed to bring him on.

While he was based in New York City, Cook had also served as the surgeon on Peary's Arctic expedition of 1891-1892. Unlike many others on the Belgica, he'd overwintered in the Arctic, living with the Inuit people and learning about their way of life.

Cook was less interested in national glory than personal glory. He yearned to actually reach the poles themselves one day, and this expedition was another stepping stone towards achieving that goal. This dream quickly made him besties with the ship's first mate...

Roald Amundsen, first mate

Ugh, fine. De Gerlache will hire a Norwegian officer, if he must. Amundsen didn't have much polar exploration experience yet. But like Cook, he had big dreams and was very, very keen.

As the expedition's third in command, Amundsen would have become leader of the expedition if both de Gerlache and Lecointe perished. This caused some consternation among the Belgian funders, who did not like the idea of a Norwegian being in charge. De Gerlache quietly reassured them that he and Lecointe would write their wills to state that command should pass over Amundsen and go to the Belgian third lieutenant Jules Melaerts instead.

De Gerlache decided not to tell Amundsen about this. Surely it wouldn't come up.

Emil Racoviță, biologist

There were several scientists on the Belgica, but I mostly want to talk about my favourite.

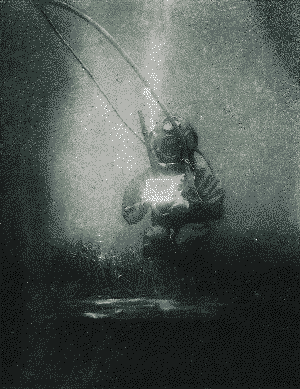

Emil Racoviță was a Romanian biologist. Here is an actual picture of him, which also happens to be the first underwater photographic portrait:

How cool is this??? Absurdly cool.

Racoviță was also an amateur cartoonist and kept everyone onboard amused by making rude drawings of them. You could argue these cartoons contributed towards the expedition's surival, as these people really, really needed some amusement (more on that later).

The Polish geologist Henryk Arctowski was a main target of Racoviță's trolling. Here's one of many drawings of Arctowski with what was apparently his defining characteristic, a gigantic dumptruck ass:

The excellent website Beyond the Belgica has many more translated cartoons which I highly recommend looking at (plenty of them also featuring Arctowski's rump).

The Belgica arrives in Antarctica

After five months at sea and an unexpectedly high personnel turnover, the Belgica finally reached the southernmost continent.

In some ways, everything was great. The expedition discovered new land and named it after Belgians. They also discovered new species and named them after Belgians. It wasn't maximum glory, but it was some glory.

Racoviță slaughtered a ton of penguins for science, but he also made funny observations about them. Here's what he thought about chinstrap penguins:

"a thin black line that curls up on its white cheek like a musketeer's mustache. This gives the penguin a pugnacious air, which corresponds well to its character"

"looked from afar like two fishmongers questioning the respective freshness of the other's merchandise"

"a strict individualist, constantly ... quarrelling to defend its property"

And on gentoo penguins:

"slightly larger than the chinstrap and more sumptuously dressed"

"decent and honest ... a shrewd communist having nothing to defend against its fellow citizens, having shared the land, and having simplified the task of childrearing by establishing a communal nursery"

(I've taken these translations from Julian Sancton's The Madhouse at the End of the Earth.)

But while the scientists were excited, de Gerlache was worried. Winter was closing in, and the expedition was behind schedule. The Belgica was also under-crewed and under-supplied. De Gerlache's plan of reaching the pole now seemed like a pipe dream. The good people of Belgium had spent a lot of money sending him down here. Would they really be satisfied with the gripping tale of how he discovered an exciting new species of midge?

And as for de Gerlache's own finances, expedition leaders often depended on publishing their stories for income when they got home. So it would certainly help to have a story worth selling...

Oops! The Belgica gets stuck in the Antarctic pack ice over winter!

It's a matter of debate as to whether this was intentional or not. But while a more cautious leader would have turned back, de Gerlache insisted on pushing his luck and sailing south into the Antarctic Circle. On 28 February 1898, the Belgica became trapped in the ice of the Bellingshausen Sea.

The crew soon realised they had no chance of escaping, and would have to spend the winter in Antarctica. This would make them the first people on record to live through an entire Antarctic winter and its polar night... but only if they lived. As Frederick Cook wrote, "We are imprisoned in an endless sea of ice ... Time weighs heavily upon us as the darkness slowly advances".

Several challenges were immediately obvious. The ship's food and clothing had not been stocked with the intention of outlasting a polar winter. There was also the risk of shifting ice crushing the ship entirely (which would be the fate of the Endurance less than two decades later). But other problems soon became evident too.

Everyone gets scurvy

Scurvy at sea wasn't nearly as big a problem in 1898 as it once had been. Steamships and other technological advances meant that people could cross oceans much more quickly, making it less likely they'd go long stretches without fresh food. So when scurvy began to ravage the Belgica, the ship wasn't well equipped to deal with it.

Although Vitamin C deficiency hadn't been identified as the exact cause of scurvy yet, it was known to be linked to nutrition. The Belgica had been stocked with lime juice, but the preservation methods had rendered it useless. Soon many of the men were very ill, including de Gerlache and Lacointe.

Frederick Cook decided to try another tack. He knew that the Inuit people he'd lived with didn't get scurvy, despite not having lime juice or any other fresh fruit and veg over winter. But what they did have was seal meat (which, unbeknownst to Cook, contained Vitamin C).

Cook proposed to de Gerlache that the men start eating raw penguin and seal meat. De Gerlache refused. Eating penguins and seals was gross and yucky and they would stick to their proper Belgian tinned food, thank you very much.

It was only when Lecointe was almost on the point of death that he agreed to try Cook's new diet. Sure enough, he made a miraculous recovery. Cook and Amundsen both pushed the rest of the crew to also eat the penguins and seals, and when everyone's physical health improved, de Gerlache was forced to concede and even ate some of the meat himself.

But physical health was just one problem to fix. Mental health, on the other hand...

Everybody goes crazy

Imagine you are stuck in the Belgica during this Antarctic winter. There is nowhere to go. It is freezing cold. It is dark all the time. The only people around you are the same people who are always around you, in close quarters, all of the time. Everyone else is thousands of miles away. You have no contact with the outside world. Your only source of entertainment is looking at drawings of Henryk Arctowski's ass.

Unsurprisingly, a lot of people started to lose their shit. Crew members developed violent vendettas against each other. Able seaman Jan Van Mirlo temporarily lost the ability to speak and hear, then insisted he was going to kill Henri Somers. Another sailor reportedly attempted to walk into the darkness, claiming he was going to walk back to Belgium. At times, the unwell men had to be locked up for their own safety.

Once again, Frederick Cook came in clutch. He discussed the men's experiences with them, finding the talking seemed to help. He also introduced a daily programme of walking around the ship in a circle, over and over again. This was known as "the Madhouse Promenade".

The circuit where the Madhouse Promenade took place was referred to by Racoviță as "Caca Avenue". This was because whatever waste the Belgica produced had nowhere to go but overboard. As a result, the ship was surrounded by frozen drifts of empty tins, animal carcasses and human waste – an ideal spot for a peaceful stroll through the perpetual night.

Cook and Amundsen are having the time of their lives

Before long, the men of the Belgica had been stuck inside the Antarctic circle for most of a year with no contact with the outside world. They were cold and filthy and their crewmates kept trying to kill them. Also the food was disgusting because the ship steward was a terrible cook and penguin apparently tastes bad. All in all, most of them were having a pretty terrible time.

The exceptions were Frederick Cook and Roald Amundsen, both of whom were having the most fun ever. The two men continued to bond, making overnight voyages out across the ice to test out designs for weather-resistent tents and dream of even more ambitious expeditions in the future.

Unfortunately, Amundsen's bliss was short-lived. In November 1898, he discovered that de Gerlache and Lacointe had agreed to cut him out of the line of succession. Amundsen was so insulted that he resigned from his post in protest.

However, as there was nowhere for him to go, he had little choice but to keep doing exactly the same job for the rest of the expedition.

Escaping the ice

The arrival of the Antarctic summer brought new hope that the ice would thaw. It even became possible to see open water from the Belgica. But the ice around the ship, now bolstered by the frozen filth of Caca Avenue, seemed as stubborn as ever.

Faced with the horrifying and potentially deadly prospect of spending a second winter trapped in the Bellingshausen Sea, the men decided to cut their way out. The crew worked long shifts sawing channels through the ice, which was now two metres thick.

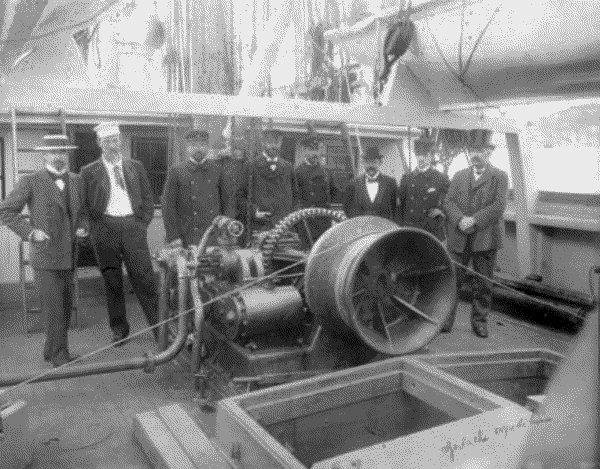

Lacointe blasted through Caca Avenue with an explosive called tonite. This was an incredibly risky job, since the ship's hull could easily have been damaged by the explosion. Instead, the worst thing that happened was that chunks of Caca Avenue rained down on everyone in attendance.

Over the first few months of 1899, the Belgica slowly made her way to freedom, finally reaching open water in March. Even after becoming free from the pack ice, she still had to navigate past dangerous icebergs – a passage the crew attempted to ease by hanging seal and penguin carcasses over her sides, which supposedly cushioned the impact of any collisions.

After the expedition

On 5 November 1899, the Belgica finally returned to Antwerp. While they hadn't made it to the magnetic pole, they still brought back GLORY TO BELGIUM and a thrilling story well worth selling.

Despite all they'd endured, the expedition had only suffered limited fatalities. Able seaman Carl Wiencke had been swept overboard in a storm before the ship reached Antarctica. Émile Danco, a geophysicist and a close friend of de Gerlache, died of a heart condition during the polar night. Sadly, the ship's cat Nansen also died a few weeks after Danco. (The number of penguins and seals killed was not counted.)

This didn't mean the survivors got off easily. Another able seaman, Adam Tollefsen, suffered a breakdown during the expedition and never fully recovered. Many others were left with lasting health issues.

For the expedition's officers and scientists, however, fame and success awaited. Many of them published their personal accounts of the expedition, including de Gerlache and Cook.

Frederick Cook especially never stopped chasing glory, although he met with mixed results. In 1908, he claimed to have been the first person to reach the North Pole, then the first person to summit Denali, although on both occasions he was almost certainly wrong or lying. He then used his (now floundering) reputation to promote a Ponzi scheme in the Texan oil fields, was convicted of fraud, and spent seven years incarcerated in Leavenworth.

I find Cook a really interesting figure. He certainly comes off as one of the heroes of the Belgian Antarctic Expedition, preserving the mental and physical health of the men in very extreme circumstances. But then his life took another turn, and history now remembers him as a scammer. His old friend Roald Amundsen still visited him in prison.

As for that ex-first mate of the Belgica... he did alright for himself too.

On 14 December 1911, Roald Amundsen and his team became the first people to reach the South Pole, achieving the dream he and Cook had spoken about on the ice more than a decade before. It's now his name that's remembered more than anyone else on this page. Some glory to Belgium... but more glory to Roald Amundsen.

More about the Belgian Antarctic Expedition

- The Madhouse at the End of the Earth by Julian Sancton – This is the book that started my fascination with the story of the Belgica. It's a great read and I highly recommend it

- The Belgica & Beyond – A fantastic website with lots of material from the expedition translated into English (including some of Racoviță's cartoons)

- Racoviță's cartoons, scanned by the National Library of Norway

⬅️ Back